This blog post was authored by Emma Nathanson, a member of the Tivnu 7 cohort from Madison, WI. She enjoys eating, running, and hugging, although not in that order. Being from the dairy state, Emma believes strongly in cheese curds and voting in every election. She interns at Street Roots and Tivnu construction.

“This is officially the apocalypse,” someone behind me remarked. I tried to laugh, but couldn’t. We were standing on the back porch of the Tivnu bayit (home), looking up at the bright orange sky. The air was thick with smoke. Inside, our power had gone out, cloaking the house in an eerie silence. To add mayhem to madness, we were still in quarantine. “Apocalypse” might have been a hyperbole, but “chaos” sounded about right.

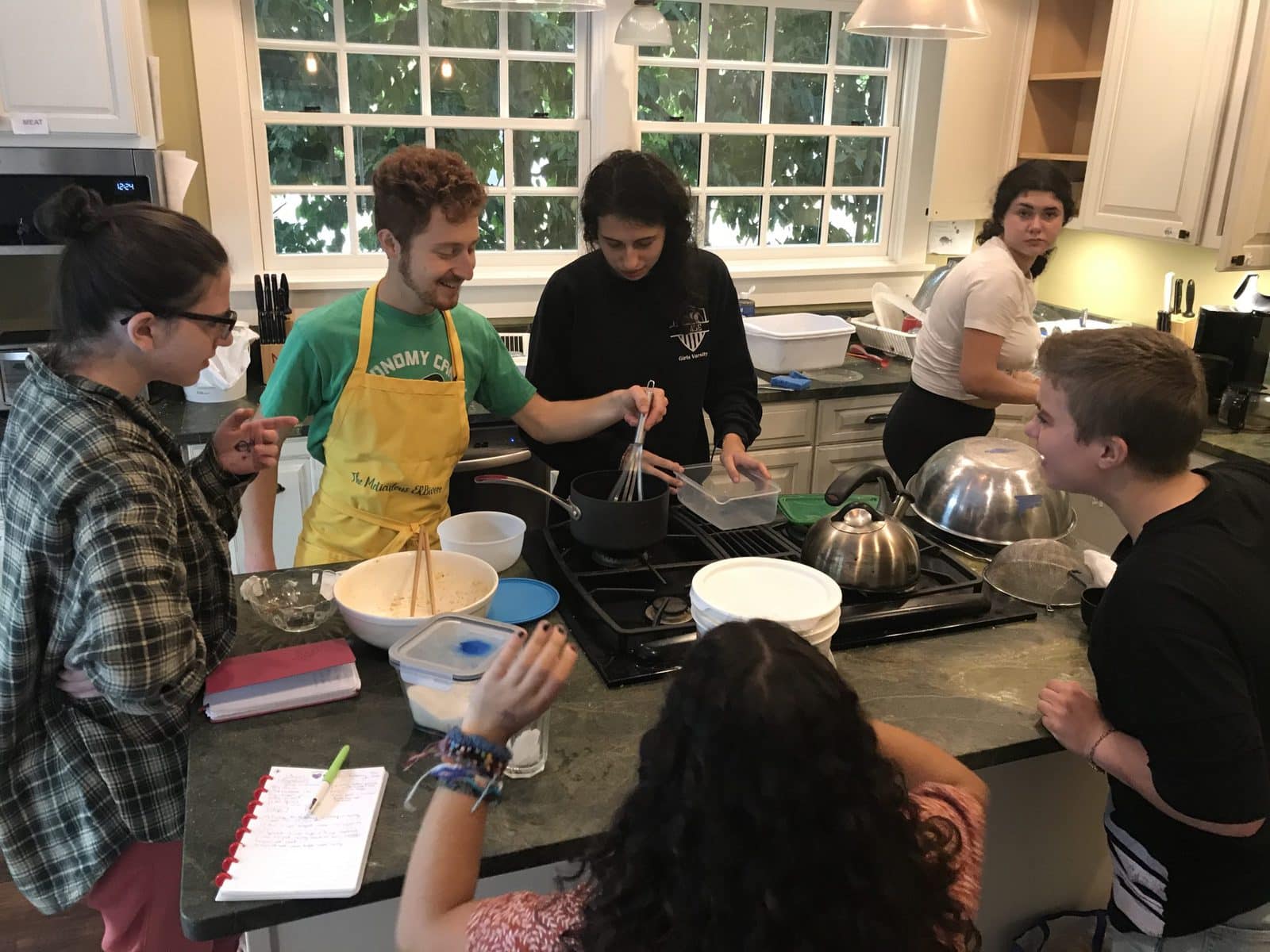

As the air quality index shot above 500–making it impossible to go outside together–and Covid-19 continued to spread faster than the wildfires–making it impossible to be inside together–we turned to the kitchen. Tivnu’s Covid protocol decreed that there could be a maximum of two people per room at all times, including the kitchen. Wanting to spend as much time together as possible, we made the rules work for us. One person collected supplies from the basement and kitchen pantries, two people bustled around the kitchen island, stirring pots and washing dishes, two people cut onions or peppers or garlic on the dining room table, and one person sat with a speaker in the hallway, serving in the honorable position as kitchen DJ. The results were delicious. Our Rube Goldberg machine of vegetables and spices produced stir-fry with tofu, salad topped with apples and raisins, turnip coleslaw, stir-fry with mushrooms, chickpea topped noodles, stir-fry with peanut sauce, coconut curry, and… did I mention stir-fry?

The complex system paid off for our taste buds and our friendships. Through meal prep, we learned more about each other’s dietary restrictions, cooking preferences, and controversial food combos. Some of us couldn’t eat gluten, some hated cabbage and olives, and some only ate mac ‘n cheese with black beans. We ate in carefully distanced seats around the living room and dining room, laughing at our meal mishaps and lamenting the orange sky outside.

Cooking and coping went hand in hand. I couldn’t ensure that none of us had Covid, I couldn’t stop the spread of the fires, I couldn’t even guarantee that I would get along with my housemates, but I could make sure that we had enough noodles to feed 13 people. It turned out that I wasn’t alone in turning to cooking during this time of crisis: during the pandemic, people across the world have found solace in sauces and hope in herbs. I remembered an article I’d read in the New York Times Magazine before leaving for Portland. Dorie Greenspan, the “On Dessert” columnist (and a Brooklyn-born Jew!) wrote about leaning into baking during the pandemic. She shared that “those of us who bake through challenges as well as celebrations know the comfort of the craft. We know that when everything is spinning wildly, we can count on butter, flour, sugar and eggs.” She also wrote about the pastry chef Joanne Chang, who turned her renowned Boston bakery, Flour, into a hub of food donations for hospitals and homeless shelters.

I was also reminded of a blog post published on the Jewish Women’s Archive blog by my friend Emily Axelrod. She wrote about making thirteen different Jewish-inspired recipes during quarantine, spanning from shakshuka to Georgian fried eggplant. At the end of the post, she reflected on the experiment: “it is through understanding the complicated origin of these dishes…and fostering an appreciation of my female ancestors that I am able to reclaim the kitchen as a Jewish feminist space.”

Both of these proudly Jewish women transformed their “hobbies” into powerful activism. They unearthed connections between the seemingly mundane task of cooking and the impactful work done by their foremothers or in their communities. I was inspired by their writing to find the acts of resistance in the food I was preparing and eating at Tivnu. Some elements were obvious: we often discussed politics and planned letter-writing parties during our meals. Other aspects of activism were buried deeper, under all the mushrooms and smoked paprika. By obeying Covid safety guidelines during a natural disaster, we stood up for the vulnerable members of our community. We demonstrated to ourselves, our families, and our neighbors that we wouldn’t let the effects of a devastating wildfire thwart our commitment to public health.

Even after the skies have cleared and our quarantine has ended, we keep cooking. We still make too many stir-fries and spend too much time anointing a kitchen DJ. We continue to keep ourselves and our community as healthy as possible.

Follow Us

Sign Up For Updates

Taking a gap year in the US can be as meaningful as doing one abroad.

Featured in The New York Times

Featured in The New York Times